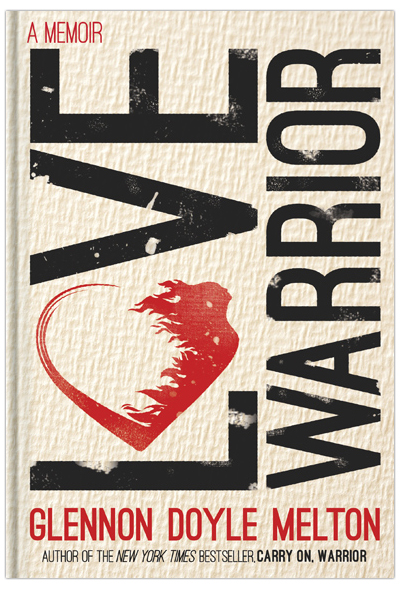

The first time I met Glennon Doyle, I was wearing pink Tinkerbell pajamas. My hair was a rat’s nest, I hadn’t brushed my teeth, and I’m pretty sure my eyes were red and puffy from crying—it’s not unlikely. I was exhausted, overextended, and overwhelmed. On this particular day, I had the house to myself, so there was ample time to get caught up on my studies and housework, but instead, tucked away in my office with a bag of plain M&M’s, I scrolled through Amazon for something to read. Crunch, chomp, munch. Red, yellow, blue. A bright book jacket rolled across the screen:

It spoke to me. Three days later, by way of modern magic, this precious little treasure arrived at my door. Immediately, I tore open the box to flip through the pages. From the start, I was hooked. Couldn’t put it down. As I read, laughed, wept and underlined passage after passage, I felt a deep connection with Glennon, a sense that we were kindred spirits.

In Carry On, Warrior Glennon candidly discusses her history of bulimia, alcoholism, drug addiction, and the unplanned pregnancy that led her to the path of sobriety. She shares her experiences of guilt and shame, and reveals her own struggle with the pressures of parenting, “wifedom, motherhood, and sober life.” Most importantly, Glennon talks about the layers of armor we wear to protect and hide.

Several years ago, seeking to connect and touch people on a deeper level, Glennon decided to shed her armor, and what happened next is nothing short of a miracle. Through reckless truth-telling, “no mask, no hiding, no pretending,” Glennon discovered she could help others feel better about who they are just by showing them who she really is—imperfect, messy, broken.

Fiercely strong, and boldly vulnerable, Glennon is a true LOVE WARRIOR.

(I was honoured to receive an advance copy of Glennon’s new memoir, Love Warrior, which I will write more about later. Available September 6th, 2016!!!)

Created in 2009, Momastery—Glennon’s Blog and online community—has since become a second home to a vast, diverse group of women seeking to genuinely connect. Momastery is a sacred space. A place to gather, rest and heal, give and receive love, and be part of a sisterhood who truly want the best for their families, their communities, and one another.

I visited Momastery for the first time after I’d finished reading Carry On, Warrior, because I just wasn’t ready to say goodbye. As I scrolled through post after post, one thing became very clear: I wasn’t alone. I wasn’t alone in my experiences, and I definitely wasn’t alone in my affection for Glennon. Not by a long shot. Her book hadn’t just spoken to me, it had spoken to countless women across the globe, and it had changed lives. In fact, Glennon’s willingness to listen to her heart and be vulnerable continues to transform lives every single day.

At Momastery—via insightful essays, the amazing work accomplished by Together Rising, as well as comments, messages, and treasured personal emails from Glennon—we are reminded, time and time again, “Life is Brutiful,” “Love Wins,” and “We Can Do Hard Things.” Through the online community she has built, women learn and grow together, challenge one another, and develop connections—as well as dreams—that go beyond the borders of Momastery. Often referred to as “Monkees,” visitors regularly meet and form friendships that provide support and encouragement through the challenges of daily life.

Many women, including myself, have been inspired by Glennon to tell our stories with far less focus on the Mask of Perfection and much more emphasis on Truth as Perfection.

Making connections is extremely important to Glennon.

I was interested to learn how she’d found her path, curious to know what inspired and guided her, what led her to create Momastery and Together Rising (formerly Monkee See-Monkee Do). So I contacted Glennon to request an interview back in November 2013, shortly after my first-ever published story, Changing My Brain, appeared in the Globe and Mail. She quickly agreed.

Caught up in an easy conversation with a woman I deeply admire, I was amazed to discover there were no uncomfortable silences between us. In fact, quite the opposite was true. Talking to Glennon felt like catching up with an old friend I hadn’t seen in ages, but loved dearly.

“What do you think draws so many people to your work?” I asked.

“I guess people are drawn to me because I’m imperfect,” Glennon replied. “Life is messy, and my honesty lets others be okay with their mess, too. I don’t profess to be a teacher, just a passionate student of life, interested every day in finding one more voice, one more piece of the puzzle. I want to let people witness my life, not teach them how to live their own lives. If a blog can show that somebody messy can still have a voice, we all win.”

I agreed.

“I look at success in terms of a day instead of a life,” she explained. “Being successful involves being authentic, where time is spent equal to your values. For me, that means rest every day, write every day, spend time with my family every day. We need to base success on what we do, rather than others’ reactions. As far as worldly success goes, you never really arrive. A blog, a book, another deal—what’s next? There’s no time when it’s actually over and you can say, ‘There, that’s it, I’m done. I have arrived.’ It really is a ‘what-have-you-done-for-me-lately’ world.”

“What’s the best thing about being Glennon, right now, in this moment?”

“The hardest thing about my life before was not being sober, not really living. In my heart, I knew I could do these awesome things, but I just—wasn’t. I was envious of others who were doing things, in a way, I felt this bitterness inside because I knew life was meant to be better, that I was capable of more, but I wasn’t doing anything. But now—total flip. I can’t possibly do more and I just hope I’m capable. It’s uncomfortable in its own way, but I think it’s better to be overwhelmed than underwhelmed—I’m constantly overwhelmed now. I want to live up to the responsibility before me. Every day, I think, what should I do to make a difference? Every day, at the end of the day, I just want to have given it all away: to be spent, exhausted, happy.”

Give what you have.

Glennon lives her life by this credo.

‘Give what you have and you will get what you need’ is a lesson taught along many spiritual paths—from 12-step programs to the Native American ‘potlatch’ or ‘giveaway’—and it’s one that she practices with great passion and dedication. In her personal life, through Momastery, Together Rising, and other online fundraising events, such as Love Flash Mobs and Holiday Hands, Glennon generously gives what she has. Every single day.

In December 2015, Glennon joined forces with Elizabeth Gilbert (Eat Pray Love), Cheryl Strayed (Wild), Brené Brown (Daring Greatly), and Rob Bell (Love Wins) to create the Compassion Collective, an organization dedicated to providing relief to refugees crossing the Mediterranean from war-torn countries, such as Syria. An online event was held to raise funds. All donations were kept to a $25 maximum. In a little over 24-hours, the Compassion Collective had exceeded their target goal of one million dollars. Relief efforts have included: floodlights to light the water at night, volunteer rescuers, heaters, blankets, warm coats, food, shelter, clothing, hygiene products, strollers, baby slings, translators, doctors, and more.

Curious, I inquired, “Can you imagine doing anything else?”

Thoughtfully, Glennon answered, “No matter what, I know I’d be writing, encouraging and trying to inspire other women, and practicing some kind of spirituality, although the form changes, as I evolve. And definitely working with children.”

“Have you always known what you wanted to do with your life?” I asked. “I’ve always dreamed of being a writer, but I wasted years ignoring that Little Voice Inside. I’d hear, ‘Write, write, write,’ then I’d think, ‘Oh, who’s going to care about anything I have to say, anyways?”

“It’s dangerous to go against that voice,” Glennon insisted. “Every time I did, things got harder. But I think I needed to learn that hard is purposeful, hard is okay. When you have a lack of faith in intuition, you look outward to others and feel like you don’t fit in; you hear outside words, words like “too much” and “not enough,” and you internalize them instead of trusting that inner voice. Trust that voice. Every single one of us is important, everyone has a song to share—the harmony doesn’t sound right without everyone. Use your voice.”

“I’m starting to do that,” I explained, “but it’s scary.”

“It is terrifying, but vitally important,” she insisted gently. “And that’s not just a theory. Everybody needs to use her voice, because we’re all stitched together. Someone always needs to hear what somebody else has to say. Honestly, there may be nothing new left to write about, and maybe it has all been said before a hundred times in a hundred different ways, but no one else can say it our way. Think of writing as singing the National Anthem. There are so many different versions, singers—it’s different every time—yet equally beautiful.”

“It’s also important to eradicate fear and jealousy,” my new friend advised, “and the idea that ‘they said it how I wanted to say it so now there’s nothing left for me to say. Honestly, those things are irrelevant, because we all have our own voice, our own way of articulating things. Maybe there really is nothing new to say, and maybe it all comes down to the same thing, but our version still matters. Different words have different meanings to different writers, readers, people… Remember, we don’t all order the same thing from the menu.”

“Do not judge your piece by how it’s taken by the public,” Glennon added emphatically. “Write for the sake of the process. I write because it changes me and my view of the world. In fact, I’d still be writing, even if no one ever read it. You have to do what you’d do anyway. For free. Given the choice to meet with my publicist or teach Sunday school, I’d pick Sunday school—every single time—because that’s REAL LIFE. Keeping my feet on the ground is important. The people I can touch keep me sane.”

“How do you maintain balance between your work and family life? Are there any tricks you’ve learned, any advice you can offer?” I wondered. “I struggle with that all the time.”

Glennon empathized, and regretfully informed me there’s no secret cure to Save-the-World Syndrome, as far as she knows. But after a brief discussion about mom-guilt, she admitted, “I do feel less guilty now. My girls watch me work doing things that inspire me, that I’m passionate about—instead of playing My Little Pony on the floor, or Barbies, which I really can’t stand—and so I think maybe, hopefully, one day they’ll be able to give themselves a break, too.”

As our conversation came to a close, I inquired about plans for the future. “So, what’s next?”

Glennon replied, “As the platform gets bigger, I just want to try to keep writing small, to remember that I’m not writing to the whole world, only one person. I want to keep meeting women who inspire, find new things to read every day, and just connect, because everybody has pieces of the puzzle.”

I was honoured to be included in that statement, and therein lies a very special part of Glennon’s magic. She has this incredible way of making everyone feel significant. Essential. One of her greatest gifts lies in the ability to remind us of the importance of connection, the inherent value in coming together to share ideas, information, truth, and love. Love, above all else. I hung up feeling as though I’d made a new friend. Perhaps not in the traditional sense—we may never go for coffee or hang out at the beach with our kids—but we’d connected on a soul level.

Several months later, I posted a Facebook status about a rejection letter I’d just received for something I’d submitted to a magazine. A few seconds later, a message popped up in my inbox:

“Rejection is one step closer, sister. Keep on. It is clear to me that this is the path for you. MAKTUB. Just live into it. It’s already done. All you gotta do is make sure your ass is in the chair and your fingers move. The rest will take care of itself. Love, G.”

Maktub, an Arabic word I discovered in The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho, expresses the idea that “it has been written by the hand of God.” While Maktub conveys a sense of fate, it also imports a sense of great responsibility, a duty to lean into your destiny. Thus, Glennon’s words held great meaning for me. Carry On, Warrior.

How does one woman be a best friend to millions? I don’t know how she does it.

I’m not sure it’s anything that can be taught, or explained, it just is. It’s a rare and beautiful quality. Glennon has a way of speaking to thousands as though she’s speaking to one. Maybe that’s the magic. The ability to regard each being as One is rooted in a powerful spirituality that involves genuine awareness and an authentic recognition of Self in Other.

Glennon makes everyone feel seen, heard, known, accepted, loved. Her vulnerability reminds us that yes, it’s hard and messy and scary to be a human being in this world, but that’s okay. We’re never alone, because we’re all alone together. Our pieces—what we have to offer the world—are what counts. We don’t have to be perfect, we just have to show up every single day.

Just Show Up.

The first time I met Glennon, I was wearing pink Tinkerbell pajamas. My hair was a rat’s nest, I hadn’t brushed my teeth, and my eyes were red and puffy—but you know what? I know she’d be okay with that. I really do.

Note: This essay is a revised, condensed, edited and updated version of a previous essay titled, “Puzzle Pieces: An Interview with Glennon Doyle Melton,” which first appeared on Living the Dream Blog, and later, on Lilacs in October. On April 9, 2022, this copy was updated to reflect Glennon’s return to her maiden name, since her marriage to the amazing and much-beloved, Abby Wambach. Love wins!

UNTAMED Book: https://untamedbook.com/

We Can Do Hard Things Podcast: https://linktr.ee/glennondoyle

(Photo: Amy Paulson Photography)